Contents

The Story of Verrlic and Durrin

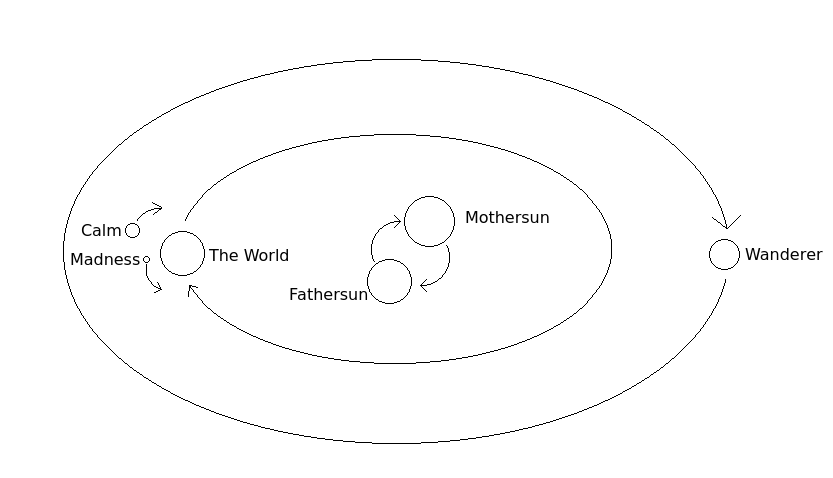

This is the solar system for the world in which my Silbari stories are set. There are three more planets (gas giants) outside the orbit of Wanderer, and two of their moons (each bigger than our planet of Mars) are visible from The World, but they are not shown on this schematic. From early in their history, the people of this world knew that other objects in the sky revolve around each other, so they never developed a geocentric viewpoint.

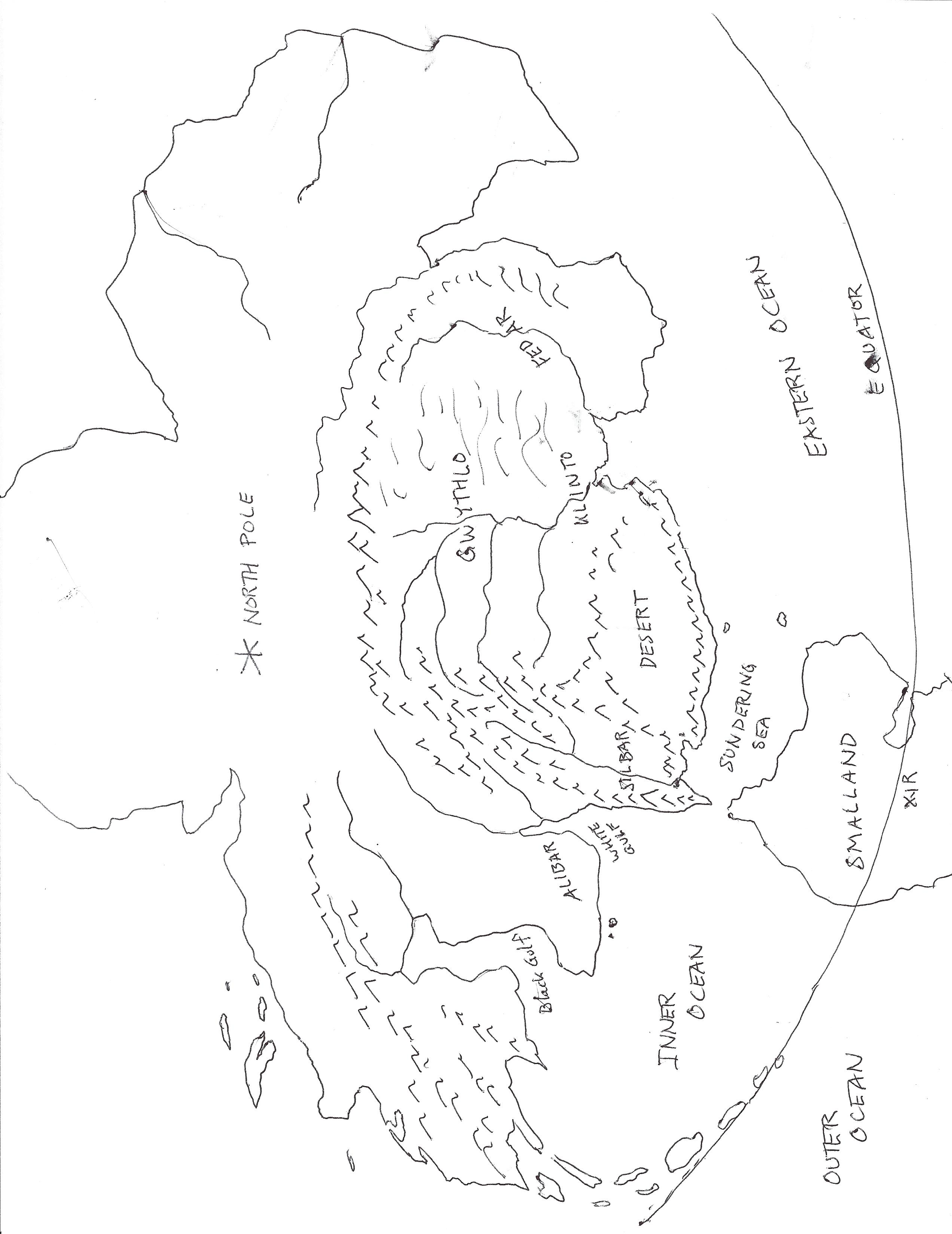

Map of Greatland

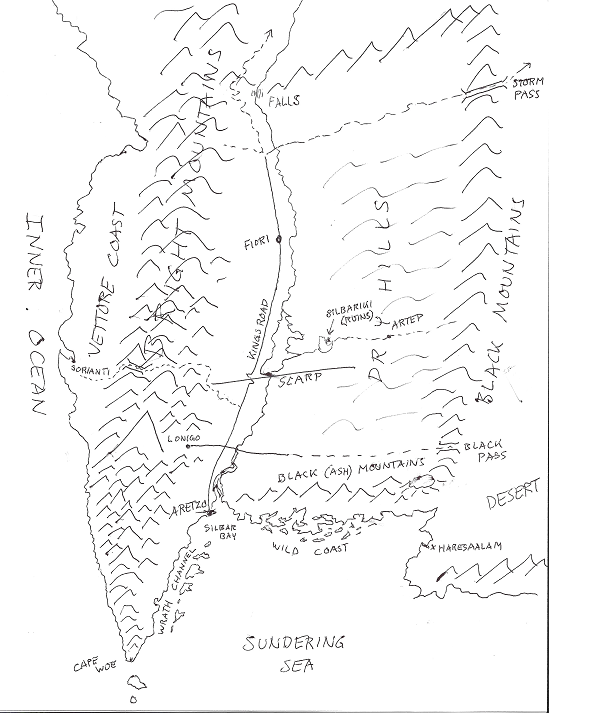

Map of Silbar

Silbar is roughly the size of California and Nevada combined, about a thousand miles from the tip of Cape Woe north to the set of canyons and cataracts known as The Falls (where the River Amm drops eight hundred feet in less than eighty miles). But the Bright Mountains are wider than the Sierras (and also taller), and their crest is more broken than that of the Sierra Nevada with a huge rainfall on the western side and the desert valley on the eastern side. Irrigation along the areas crossed by the Kings Road supports the country’s comparatively large population.

The Dry Hills (actually a chaotic set of low mountain ranges and basins much like Nevada) have many small pockets of arable land but none big enough to serve as anchor for an independent kingdom, so the Silbaris have long dominated all the ethnic groups of the Hills. The Duermus are the largest of these folk; ‘Duermu’ means ‘coward’ in Old Silbari, so it is not a name that the tribe took willingly. Their seat of power is in the small fortress and community of Artep, carved into the walls of a sandstone canyon in the hills. They are not always treated well by Silbaris, who relegate them to grave-digging, garbage-hauling, and similar low-status tasks.

The Black Mountains are actually a broken mass with many side-ranges, similar to the Southern Rocky Mountains of Colorado and northern New Mexico and southern Wyoming but with a more pronounced central spine. The two easiest ways to cross – Storm Pass and Black Pass – hold old trade routes and roads, shown on the map, and are the practical places to cross. The few passes in between these two are higher, more prone to snow, and drier, with less water for the men and horses needed for an invading army.

The Sacred Mountain, generally just referred to as ‘the Mountain’ with emphasis to convey the capitalization when speaking aloud, is also less reverently known as God’s Footstool. It rises over 29,000 feet high just west of Lonigo (big triangle on the map). Nothing else in the Bright Mountains tops 15,200 feet, though there are five 15,000-footers. There are a lot of little valleys in the mountains that support limited agriculture (mostly barley and other short-season crops, since winter is harsh, and lots of sheep and cattle). The Dale-men (as they are called) who live there tend to be bigger than ordinary Silbaris and more frequently have black hair.

Peoples

Silbar is occupied by a relatively homogenous population, the overwhelming majority of which (+85%) shares a common ethnicity, language, religion, and culture. They are mostly brown-skinned, brown-haired, and brown-eyed, with comparatively little visible variation (unless you are one of them, in which case you’ll notice lots of minor differences that an outsider generally misses). They arrived in the valleys of Upper and Lower Silbar several thousand years ago as slaves taken from the deserts by the then-dominant resident culture. They then multiplied and finally overwhelmed and absorbed the previous population, though along the way acquiring a strong dislike of slavery and a cultural and religious bias against it. Around then they invented irrigation (or rather the previous society did, and took them as slaves to operate the expanded farmland), and they subsequently grew so numerous that they have outnumbered their neighbors and hung onto the Upper and Lower valleys ever since. In the time of our stories the Silbaris number plus or minus 20 million people total, including ten and a half million in Lower Silbar, seven and a half million in Upper Silbar, half a million on the southern peninsula, and a million on the Vettore Coast (those are more ethnically mixed than the populations of Upper and Lower Silbar); the remaining half-million are scattered east across the deserts and the Black Mountains in small valleys.

The people of Silbar speak a basic language called Silbari that has relatively modest dialect changes across it, surprisingly small changes for the sheer size of the place, but there is enough difference that a man from the Vettore Coast will have a noticeably different accent than one from the mountain dales or a flatlander from the irrigated valley, or a hardscrabble village in the eastern part of the country. They are also a literate culture with a written religious text that has many laws. They follow a syncretic religion that has a central dominant deity that is never directly named (because the name is too holy). This Lorran religion is nearly monotheistic but includes several attendant ‘seraphs’ or angelic semi-gods that are really older religions that were long ago subsumed and demoted to ‘subordinate’ status. Silbaris pray to the Great Seraphs – Father Haroun the Defender and Mother Umana the Healer – for intercession with the One God, but rarely pray to The One directly; it’s regarded as presumptuous. One might also pray to the Evil Seraphs if one wanted something – Salim the Tormentor, master of the Pit of Hell, for vengeance and other bad things, or to Desrey the Temptress, mistress of emotions, to attract someone to you who you want (but who may not want you). This is socially frowned upon; from infancy a Silbari is taught that the Evil Seraphs only make bad bargains and cannot be trusted to keep the ones they make.

The social system is organized as an aristocratic hydraulic despotism, actually two – one in Upper Silbar and another in Lower Silbar, though intermarriage long ago unified the country and it has generally stayed unified ever since. Control of the roads and the irrigation systems is a prerogative of the monarchy and is used to hold the nation together. Since even the peasants possess basic literacy (though seldom any more than is required to read the Writ in Temple), there has been less oppression than there might have been, but this is not a utopia. Social classes were still relatively stratified until very recently, with only slow movements between them – but the social pyramid has a base in freedmen, there is no slavery in Silbar because of the cultural baggage of being former slaves themselves, slaves who overthrew their masters. This has some odd consequences – only peasants can own farmland, for example, even though the nobility has a claim on a percentage of the output (traditionally one tenth, with the religious hierarchy claiming another tenth). Even vast irrigation projects feed only small farms, not plantations, which makes mobilizing capital more difficult. But this rule also puts a floor under peasant poverty – so long as one has farmable land, one has status and some kind of income. Primogeniture has prevented the land from becoming hopelessly fragmented, while also creating a continual flow of landless younger sons into the trades, the cities, and the military.

Rootless children of landless families have for a long time tended to accumulate in the cities, which are not nearly the swamps of disease that they would have been in our world (more on this below). Cities are sometimes quite large and have predominantly a trading relationship with the countryside rather than a parasitic relationship – the cities are generally craft manufacturies and mining centers making goods, which are sold to the densely-populated countryside as well as to each other. This has long resulted in Silbar being a net goods exporter, the first majority-urbanized culture on its planet, with a gradually rising middle class. Silbar has been an unusually stable society for much of its history, at times calcifying towards a caste system but always being jarred out of its complacency by some traumatic event, such as earthquake, drought, volcanic eruption, plague, civil war, or invasion, all of which brought back a degree of social fluidity. In this time, rising trade and the growing middle class shelter under the umbrella of Imperial Conquest (more on this below), with grave stresses on Silbar’s self-image and internal peace.

Culture

A couple of cultural peculiarities require special mention. Religion in Silbar is a female practice; religious leaders are usually exclusively female Priestesses (and the Autarchs and Hierarchs that oversee Priestesses, which are more or less the equivalent of Bishops in Christianity but with some differences that can surprise the ignorant). Government or politics is a male practice; rulers are generally exclusively male Kings, Dukes, and others. War (killing, destruction) is viewed as an exclusively male prerogative, while healing, nurturing, and teaching tend to be viewed as female prerogatives. That said, men also plant, design, and build, and women also judge and execute. Indeed, Priestesses that know healing arts can also kill you just as dead as a man with a sword, and less messily. If you are brought before a Priestess for judgment in a criminal case, and the sentence calls for death, she may have her male bailiffs hold you while she kills you with a touch. (Note that this means Magic is a fundamental feature of this society.) Since both sexes are expected to read and write the Writ (Holy Book), and since Priestesses long ago learned tricks of how to control female fertility and a fair amount of medical comprehension, Silbari women have long been freed from the slavery of constant pregnancy. With the most advanced medical knowledge on their world, they lost fewer children than other peoples, so they could afford to have fewer to begin with. This resulted in women being partners to men in the society, but within highly-gender-dependent roles. ‘Equality’ is very relative, and this is a society with powerful gender-prejudices. Silbaris can seem very enlightened and also appear to be knuckle-dragging bigots at the same time.

This state of dynamic tension between the powers of the sexes is culturally regarded as both necessary and very desirable, so strong cultural barriers exist to bar transgressions except under temporary or highly abnormal situations. The few historical examples of transgendered religious or political leadership are all either cautionary tales of disaster or involve periods of genuine crisis where temporary role reversal cured a specific problem. As a result, any perception of increasing gender-role reversal is “Viewed With Alarm” in mainstream Silbari culture, as a harbinger of troubled times. That said, there have always been a minority of people who don’t fit society’s expectations and Silbaris have evolved peaceful ways of coping with them, some rather bizarre to an outsider’s eyes. The rare male doctor will wear skirts and a facial veil, will shave and grow his hair long just like a Priestess (or wear fake braids), even though it is obvious to anyone listening that this is a man. The rare female practitioner of a male art (such as a logger or miner) will wear trousers or a male loincloth and tunic, an uncovered face in public, and at least cut her hair. She will thus be accepted regardless of her body shape – which most Silbaris simply will not “see”.

This also means that professions that involve both men and women doing them, are culturally a little ‘suspect’ in Silbar. Acrobats and actors (which tends to be a single category in Silbar) may be of either sex but are always perceived as somewhat ‘other’ in the society. This does not prevent their performances from being popular – indeed, the good ones are well-attended and make a comfortable living - but you wouldn’t want your child to marry one.

Marriage is strongly favored in the culture – it is expected that everyone will marry unless they choose a celibate status like a monk or nun. Priestesses are required to marry unless they become celibate nuns, and the paths to power in the religious hierarchy are mostly reserved for mothers. A young man who isn’t married by age 30 is either 1) a monk, 2) desperately poor or 3) has some unattractive physical or moral feature. A woman who isn’t married by age 30 is similarly slighted, unless she’s rich (or a nun). Widowhood, on the other hand, is an acceptable reason to not be married, and there are epic tales and songs about true loves that refused to marry again after their partner died. Silbari men will slash their sideburns (just in front of their ears) if they are widowed, as a visible sign of their status and their grief (the scars usually make the hair grow back out white over the scar). Women will braid their hair differently if they are widows. However, many more widowed men and women do remarry than remain single. Marriage is noth an economic advantage and a comfort, and most will seek it.

Plural marriage, however, is highly frowned upon (though it is not actually forbidden). But a Silbari would have to endure significant prejudice from neighbors if doing it. The Priestesses are well aware that having a significant population of young men who can’t get wives because the young women are being monopolized as second and third wives by older men, creates a violent society. Quite a few Priestesses would flatly refuse to perform a multiple marriage. There is no advancement within the religious or political hierarchy for someone in a multiple marriage, and choice of professions could also be severely limited. Many cruel jokes are told about multiple-partner relationships, partly as a means of discouraging them.

Magic

Magic is present in this world. Mages (male) and Priestesses (female) draw upon flows of raw power in the fabric of the land and seas. The Power than sustains spellcasting wells up out of the interior of the planet, and once used it sinks back down into the World, expended. Magic is classed into two categories – the Four Elements (male) and Life/Death (female); see more detail below. The ability to use magic is genetic, those without the necessary capability simply cannot cast spells. These abilities are called ‘Talents’ in Silbar and many other nations, and various classification systems have developed to reflect differential ability.

One odd quirk is that a very few people are born with essentially an immunity to magic; spells thrown at them do not work, they are not affected at all. The gift manifests at puberty and the stronger inheritors of this ‘Gift’ can even break spells that are simply cast _near_ them, or break a ‘group’ or area-of-effect spell even though other people in the area of effect would otherwise have been affected. In Silbar this is called ‘Haroun’s Gift’ and is thought to be given by the senior male seraph of the main religion (Haroun the Defender). Since even the most powerful mage is essentially helpless against a warrior with the Gift, mages do not rule The World (though they may rule individual nations). Military organizations usually recruit men with Haroun’s Gift as officers, because the stronger ones can protect their men from area-of-effect spells.

Ability to use magic is highly sexually segregated in this world; that is, what one can do is linked to one’s sex. Men generally can manipulate the Four Elements (Earth, Water, Air, Fire) and the great majority of magics are ascribed to one element or another (or to combining two or more elements). Women can manipulate life and death; they can Heal (or kill with a touch), they have the ability to Diagnose a being’s ills, they can exercise an Empathy with a being that lets them understand what is going on in the body and even influence it a little (in an extreme form this becomes Truthtelling – the Priestess is sensing the internal stresses from trying to withhold truth), they can Call or Banish supernatural entities (of which Silbar has more than is comfortable), they can manipulate living things from bacteria up to the largest of creatures (the legend of Jinaha Whale-Rider is still told on the Vettore Coast).

So male magic-users are called Mages and female magic-users are called Priestesses. Note that many minor magics can also be done by Priestesses, but they are severely limited – many priestesses can light a candle, none of them can cast a twenty-foot-long flamestrike (like a flame thrower), which is one of the tests for advancement to the Mageguild, which is known as the Council of Colors in Aretzo.

They have competing organizations – in Silbar the Mage Guild is all male and the Temple Hierarchy is all female. But it is known that magic has a hereditary component so Mages and Priestesses tend to marry each other, so as to produce children with stronger magical Talents. This puts a natural check on the possible rivalry between male and female magic users. It also has tended to concentrate and strengthen the magical Talents over time, until over 2/3 of the Silbari population has at least a little magical talent (generally very little, but sometimes the kids surprise you). The Mage Guild ranks boys with magical talent through a testing system; over time some develop their Talents to a very high level and progress through the ranks from first (lowest) to eighth (the Council of Colors). Most are essentially genetically limited to lower levels and will be only able to do one or a few magical things, often with only one of the four Elements.

In most families, female magic talent tends to alternate generations. (Male magic is closer to consistent, but can still fluctuate over generations, just not as much.) A woman with strong magic can expect that her daughters will have weak (or even no) magical talents, but her granddaughters will have strong ones again. This problem creates considerable stress across the generations; strong Priestesses tend to regard their daughters as merely vessels to produce granddaughters. This does not go over well in terms of maintaining familial peace! It is very rare for female magic to breed true in the second generation, with a daughter as powerful as her mother. In the rare circumstances where they are, the pressure to breed is even stronger, so that the trait can spread. So-called ‘even-daughters’(second and fourth and sixth and eighth generations) are sometimes very resentful over their lack of magical talent.

Spiritual entities plague the World, ranging from passive Living Shadows that tend to stay in one place but devour magic (and magic users), to full-on Demons summoned out of Hell (and dozens of types in between). A Priestess can banish them, but it takes Power and a more powerful entity may not be able to be banished by a too-junior priestess (which can be a very nasty situation indeed). Shadows are normally sedentary and comparatively easy to Banish, Demons are mobile and very hard, and any kind of spiritual entity may be hard or easy to detect or to banish.

Other Ethnic Groups

There is a subject population of distantly-related peoples within Silbar, they are called Duermu (means ‘coward’ in the ancestral Silbari language) and they dwell primarily in the desert hills east of the river Amm. These tribes shade through several intermediate ethnicities and into other completely different ethic groups as one crosses the three-thousand-plus miles of desert hills and valleys running due east of the River Amm. The sharpest change is at the Black Mountains, where the Duermu nearly cease and other groups become dominant, though very small isolated groups of Duermu are still found all the way east across the desert to the southern edge of Klinto. Thus, the Duermu can be said to be mostly confined to the lands east of the Amm, west of the Black Mountains, north of the Ash Mountains, and south of the Falls area that rises toward mountainous territories of Cythera. Duermus are also brown-skinned but more of a copper color than Silbaris, they have much darker hair (generally almost black), and their eyes may vary substantially in color but mostly have gray or orange tinges. They have a single eyebrow running across their foreheads, with no break in the middle like most people have. Their language is distantly related to Silbari but not readily intelligible to a Silbari speaker without practice, and they use a radically different intonation and grammar. Functionally, they don’t speak the same language.

At the north end of the Klinto Gulf (northeast of the long desert, over 3,000 miles east of the River Amm) live another people that are commonly called Klintos, they are much paler of skin than Silbaris or Duermu. They are also notable for having generally black hair and eyes, and a cartilage fold at the top of their ears that makes the ear look like it has a point. This is generally a recessive genetic trait but it is sufficiently common among Klintos that the majority of their populace carries it. Silbaris regard it as a mark of demonic parentage, the evil imps and demons on paintings in Silbari temples always have pale skin, pointed ears (usually very exaggerated), and black hair and eyes, caricaturing the typical Klinto appearance. This may be traceable to ancestral Silbaris originating in the eastern end of the desert and being forced west by Klinto depredations, carrying the cultural baggage all the two-thousand-plus miles to Silbar. The Klintos became significant seafarers around four hundred years ago and began to clash with Silbaris in the Sundering Sea, as well as with other groups. Klinto pirates and slavers became a serious threat more than two centuries ago; they would raid the islands and sometimes even the coastal towns and make off with slaves, which they sold in their own country or to the Xir in Smalland (see below). A few generations ago the Klinto aristocracy intermarried with the rising nation of Gwythlo to their north and west, and thereby passed on these physical traits to the Gwythlo leadership, save the black hair.

North of the desert, Greatland rises into interior basins and hills sloping downward to the east and rising on the west towards the heights of Cythera, which is essentially a high plateau crossed by multiple chains of mountains (it is the seam where the two tectonic plates that make up Greatland are colliding and squeezing the granite crust upward). This area is dominantly mountain forests and basin grassland on the west and it slopes down through savanna and pocket shrublands into hardwood forests at the lower, eastern elevations, where one of the great rivers gathers waters from many tributaries to run all the way from Cythera to the Klinto Gulf. (Think of the central USA between the Rockies and the Appalaichan Mountains.) The grasslands and forest have recently become dominated by the Gwythlos, a northern tribe that came south and invaded the central part of Greatland. Though the Gwythlos are militarily and politically dominant here, they are actually a rather small minority, ruling a maze of subject peoples of at least fifteen different nationalities from Naibers in Cythera to Fedarans in the other large river valley east and northeast of Klinto. Gwythlos have relatively pale skin, rather like a northwestern European in our world, but they often live an outdoors life that tends to tan them (or redden them, as the case may be). They are usually light-haired, many blonds but with a sizable minority of lighter browns and a much rarer minority of black-haired members. They tend toward blue or green eyes.

Gwythlos are primarily a horse-culture that were originally herdsmen but also became farmers and adapted well to the wider landscape of central Greatland. They have a feudal society of vassalage and lordships, but with a strong tradition of independent thought and respect for ability that keeps their aristocracy somewhat fluid. The independence means that a free man can switch his allegiance to a different lord any time he wants, though doing it more than once a year or three times in your life is severely frowned upon. (The tragic tale of Yarik Five-Lords is a cautionary story much repeated.) Cities are a new experience for them, and they tend to be suspicious of them and not very happy there. The Gwythlo social system doesn’t adapt well to city life and tends to devolve into gangsterism and warlordism. Gwythlos think in terms of dominating territory and accruing a clan about a charismatic leader, which makes them hard to organize for large-scale settled living – young men have too much tendency to hare off after the latest hero of a ballad instead of staying home to mind the farm or tend the herd. Gwythlo language is rich in poetic terms for horses and emotion, but relatively impoverished for intellectual concepts, so it has borrowed heavily from the Silbari and Klinto languages for words (rather like Russian has done with English in our universe).

The fifteen or so subordinate populations within the Gwythlo Empire, and the other nationalities and ethnic groups of The World, are not discussed here.

History

The Story of Silb

Silbar is an old society; Gwythlo is a young one. Silbar’s long past shapes both in ways that many know nothing about.

Silbaris were originally known as Sorrites, desert dwellers who herded goats and sheep and wandered far. They originally came out of the desert into the Valley of the River Amm to trade with the people there, the Ammites. It wasn’t uncommon for Ammites to take them slaves on raiding expeditions, especially after the Ammites invented irrigated agriculture more than 45 centuries ago. Ammites enslaved vast numbers of the Sorrite desert folk to till their farms. This caused much hatred. In time the Ammites became a brittle upper class living in palaces and cities with a resentful underclass of Sorrites to raise the food, hew the wood and draw the water.

Then a great plague swept the Valley of the River Amm and a full two out of three of the Ammites died of it. The Sorrites suffered too but not as much, there was rebellion, but the Ammites had the discipline and control and were slowly putting down the rebellion. Word of it spread to the free desert Sorrites. Silb, a young warrior-leader, called any who would follow to join him in an attack on the Valley, to free their brethren and take the riches of the Ammites for their own. Many followed him, ignorant of what they would face but restless and curious.

They gathered at the east foot of Black Pass and climbed up to it; the way was hard, for in those days the eastern approach was all rock, sharp black obsidian with a narrow path through it. The Ammite garrison at the top repulsed them and they fled back down to the sand.

Then Silb prayed to their God for help, and a great sandstorm blew out of the desert. It piled sand against the Pass, burying the sharp obsidian and opening a broad front of safe footing along which the Pass could be attacked. Silb called his followers to attack again. Some refused, but most agreed to follow him again, and they swarmed the fortress under and butchered the Ammites. The door into the land was open.

Then, from the Pass, they looked west across hundreds of miles of Silbar and beheld the top of the sacred Mountain. It towered so high that even though all the rest of the Bright Mountains were below the curve of the horizon, its peak could be seen. And from that peak unrolled a banner of windblown snow that took the shape of a giant hand and beckoned them forward, into the new land.

(Later scholars pointed out drily that the Mountain is in fact invisible from Black Pass, it is not until one gets another three hundred miles west, past Sulmona, that it can be seen, and then only from the highest hills. Some scholars claim that Silb and his people wandered for years in the upper reaches of the Ash Wadi before they came far enough west to climb a high ridge near the present Caravanserai of the Singing Stone and finally see the Mountain.)

Some Sorrites quailed at this fearsome display, declaring it was the Ammite Gods beckoning them into a trap. They refused to go forward. Silb cursed them, calling them ‘Duermu’ or ‘Coward’, and led the rest of his people to where the hand beckoned. They found a land torn by war, and they piled onto the cities and Ammite manors in quick raids and huge slaughters until they had taken all of the country. From the giant Falls where the river flowed down from forested Cythera, to the distant southern seacoast, the Sorrites conquered all. They renamed the land ‘Silbar’ and themselves ‘Silbaris’, married with their kin already there, and subjugated the Ammites so thoroughly that they never rose again. In time the Silbaris absorbed them and nothing remained of the Ammites as a separate people. Silb settled in an oval valley to the east of the main river-valley, where a crescent lake of brackish water bred great flocks of birds and crocodiles, and antelope for the hunt. The site of his last encampment became known as Silbariki, the Place of Silver Birds.

The Story of Verrlic and Durrin

In time Silb’s people extended their sway south into the isthmus connecting Greatland and Smalland, for in those days the two continents were not separated but instead joined. The mountains chains ran south with only one gap, and that still two hundred feet above the level of the seas on either side. But the two seas were only sixty miles apart and this gap was the easiest way to cross between the Eastern Ocean and the Western one, and so for generations trade had flowed across it. The spreading Silbaris took the coastal cities on either end of this trade route, made them their own, grew fat and corrupt on the wealth, and forgot who they were. Five hundred years after Silb led his followers into the Valley of Amm, the Silbari kingdom had its capital at sprawling Radagashta on the south-east coast, and was decadent and lazy.

Then a Mage discovered how to tap the power of Nodes, and proposed something audacious. He proposed to magically dig a canal from the east to the west straight through the Gap, connecting the coastal ports of Radagashta and Chivishta. By magic, and overnight.

At the time the Royal family had twin sons, Verllic and Durrin; Verllic was the elder and had been raised to become King after his father (for there was no Crown in that time). Durrin was loyal to his father and brother, hard-working and yet serene and happy. They shared a unique gift – they could speak mind-to-mind. They grew up very close because of this. Yet perhaps that very closeness betrayed them in the end.

Their mother died when they were not yet fifteen, and their father mourned her for the rest of his life. He grew more and more detached from daily living, offering sacrifices in her memory and neglecting the duties of the Kingdom. His sons, also hurting over the loss, were also neglected and sad. Durrin tried to cheer his father up, draw his attention back to life, get him to do something to remind himself of happiness instead of sorrow. But their father persisted in his melancholy, and so more and more of the kingdom’s work fell upon Verrlic, who was not adverse to running the country in his father’s increasingly-frequent absences. The two sons kept in touch through their mind-link, but spent less and less time with each other as each struggled with his chosen task. And failed to realize they were drifting apart.

Verllic listened to the radical mage, and gradually become convinced that he was right. Dig the canal, trade would grow, more wealth would follow, all would be well. But his brother argued the path of caution – where would the dirt and rock go? How would the spell be anchored? What if it got away? Perhaps it would be better to start with smaller projects and gain experience. There might be something they didn’t know, and needed to know. The two argued endlessly inside their heads, tussling like young cats. Durrin gradually grew distracted by his ever harder struggles to get their father to focus his attentions upon life – and Verrlic took advantage of that distraction to talk to his brother less and less often.

Verrlic had quietly decided to reject the counsel of caution, but while his father still ruled he lacked the authority to order the canal to go forward. Wanting to secure the glory of a spectacular accomplishment for himself, he began to hide his mind from his brother. They were speaking less and less frequently as their separate burdens drew them apart. Verrlic refused to attempt smaller deeds; he would have all or nothing. Then his father grew sick, and died, and Verrlic succeeded to the throne. Durrin, exhausted and heartsick, threw himself into arranging his father’s funeral, for his brother the King was too busy. Durrin, loyal Durrin, in between his many distractions, still counseled patience, wait until after their Father’s funeral and burial in the Valley of Kings where the last three hundred years of kings had been buried. Verrlic, reluctant, agreed, but stayed withdrawn from their former close companionship. His agreement was false, he only bided his time.

So Durrin took his father’s body, embalmed against the heat and humidity of south-coastal Silbar, north toward the Valley of Kings, and laid their father to rest in the tomb that had been prepared for him there. And while Durrin tended to this final farewell, Verrlic deliberately shut his mind, set aside his inconvenient promise, and ordered the spellcasting for the canal to begin.

It took six days, and for the first five none knew what the Mage did save Verrlic, until the spells began to act. New fissures opened in the Gap. Caravan traffic halted and then retreated. Word spread, and Durrin, exiting from his father’s tomb in the Valley of Kings, discovered his brother’s perfidy on the ninth day. He tried to call to him and received no answer. There was no time to reach home, so he hastened to the City of Cull on a promontory above the River Amm, the last high ground before the interior Valley flattened into the coastal plain and its teeming population. He climbed a conical hill outside the city, from which one could see far south, and sent his thoughts to his brother in distant Radagashta.

“Wait! You promised to wait!”

Verrlic, angry and half-ashamed, spurned the message and ordered the spell accelerated. The mage hastened to comply – and lost control of his spell. Durrin, terrified at what might happen, was now the less-frightened of the two, as Verrlic’s palace began to shake apart around his ears.

Earthquakes rocked the coastal plain. The canal was already forming, the west end had collapsed into the ocean and the Western Ocean was reaching for the Gap now. Shock waves were rattling Chivishta so badly that folk fled the city for the northern mountainsides. The Gap sagged lower until the sea invaded it. Then as the Mage’s control failed, the spell broke free of its anchor in Radagashta, and lashed the coastal plain.

Durrin, perceiving the failure and massive calamity about to befall his country, prayed to the One God to pin it down again. Better a massive trench in the wrong place than the countryside gouged and torn randomly across a much larger area.

His prayer was answered, but not the way he wanted. The east end of the canal spell seized upon the River Amm just south of the Hill he stood upon, and it split the plain diagonally. Flatlands were cloven from foothills and foothills themselves riven. The flat coastal plain, home to millions, dropped below the waves, and save for a few hilltops the waters rushed in to cover it. The backbone of the mountains broke, sagged, fell, and the two oceans roared together in howling ruin. Smalland was sundered from Greatland and the seas connected across the sunken land. Silbar’s people found their numbers reduced by half.

And Durrin felt his brother die in bewildered, shamed failure.

Durrin cast himself upon the ground and wept atop the conical hill. He called upon the God to save something from the marching waves, that looked set to flow inland and fill all the Valley right to the toes of the Sacred Mountain. The One God heard him and was merciful; though the lower half of Cull was drowned, the greater part of the faithful city’s people escaped. The waters carved a great bay in front of the city, and then fell quiet. Durrin’s prayer had saved his people.

When at last he raised his head from the stony top of the Hill, he found that his tears had turned to silver. He collected it and fashioned a crown of three simple circles, to remind himself of what had happened, and set forth to put the land back in order. And in so doing, made the Pact With The God that has governed Silbar ever since. Durrin built a stone chair atop the Hill, named it the Hill of Sight, and renamed Cull the Arisen City, or Aretzo, making it the new capital. Close enough to the dry irrigated valley that its hot breath could be felt in summer, and close enough to the sea to remind Silbar of its tragic loss. The sea, that now stretched hundreds of miles farther west to connect to the western ocean, was renamed the Sundering Sea, and the whole event referred to simply as The Sundering. In time his descendants built a palace on the lower slopes of the Hill of Sight and the city of Aretzo grew out and around it, converting the sunken parts to a great harbor. Later still mages in his line discovered how to tap the Node under the Hill itself, but that is another story.

The Story of Azerin and Zablock

Many thousands of years after the Sundering, the capital had been moved again – to Silbariki, the old camp where Ancestor Silb had died. Irrigation works had been cut into the oval valley and made it bloom, the lake was no longer so brackish and the entire east bank of the Amm was now an irrigated paradise from the Storm River in the north to the Ash Wadi in the south. Silbar regained its former population and more, but was inward-looking now. Trade sailed through the gap where once the coastal plain had been, that now lay eighty feet and more beneath the waves. But trade funneled through Aretzo was taken for granted in Silbariki, seen as nothing more than revenue to be spent upon pleasures. Once again, the Kings of Silbar had become decadent and corrupt, isolated from their own people.

Silbariki had grown into a sprawling city upon which the kings lavished the best in architecture and art. Whole mountains of marble were plundered for its public buildings and spaces. Pleasure boats drifted on the crescent lake, where spells kept the marsh caimans away from their occupants. Priestesses dominated the kings, keeping them weak and inward-looking while the real power in the country lay in the Hierarchy’s hands. Missions went out into the world to spread the Silbari faith (and found many listeners ready to convert, for Silbar offered a way to interpret the world that made more sense than most faiths). But at home the country froze into a stasis where problems were not solved, but merely ignored.

Then twins were born to the Royal family, identical as two peas in a pod and impossible to tell apart – and the nursemaids confused them. Which was older? Who was who? The family dithered and the nobility sought advantage. As the years passed sly whispers in the boy’s ears lead them to doubt each other even though they could hear each other’s thoughts. Childhood love for each other grew into resentment and finally hate, and with it a rivalry that became more bitter with every passing year. Faction split the country. The weak king dithered, avoided the problem, and let it grow. His only daughter tried to ease her brother’s rivalry only to be banished to the north through a forced marriage.

Then the king died, and the Twins went to war. Each sought to prevent the other from claiming the Crown, yet each secretly feared to try to take it for himself – for if it judged him not worthy, it might kill him. War raged across the land and cities were sacked, canals broken, famine spread, and destruction grew ever more violent.

Finally the armies confronted each other between Silbariki and the River for a deciding battle. And now the God to a direct hand, splitting the valley itself in a giant earthquake that literally separated the two forces, Azerin’s lifted up on a rearing block of terrain and Zablock’s knocked sprawling by the sudden drop of the land they stood on. But Azerin launched himself off the resulting Scarp and fell upon his hated brother, and both died. Their sister took up the crown instead and set herself to healing the wounds of the war.

In time the river, backed up behind the dam-like Scarp, formed Purification Lake and overflowed into the old channel through a new 60-foot waterfall. The lake covered the battle site and it lives now only in memory – and in the very real Silbari fear of Royal Twins.

Gwythlo’s Rise

Gwythlos respond to charisma and personal loyalty, but also have tribal dynasties that, through intermarriage, have produced a line of great military kings and finally an Empire spanning the center of the continent. Through absorption of Klinto, Fedar, much of Cythera, and parts of the desert they came in conflict with Silbar, and shortly before the main characters of these stories were conceived, the Gwythlo Empire conquered the Silbari Kingdom. This gives the Gwythlo Empire nearly a third of Greatland’s land area and almost half of its people (roughly 100 millions out of just over 200 millions on the continent; a fifth of the Empire’s population lives in Silbar), making it the largest Empire on The World. In fact, it is probably too large to effectively administer by people who only have horses and sailing ships for communication, and thus during the time of our story it has begun to fracture around the edges.

In a great irony, it was the healing and reproductive-control techniques that the Gwythlo women learned from Silbari priestess-missionaries a few generations ago that enabled Gwythlos to enjoy the sudden population expansion that gave them the men to defeat their neighbors and create their Empire. There is considerable religious stress in Gwythlo now over the role of (and relationship to) Silbar, for old-time Gwythlo religion is essentially Druidic and worship is primarily placatory towards a malevolent pantheon of mutually-antagonistic deities (some of which Silbaris would frankly classify as demons, not gods). Silbari priestesses are persecuted in some parts of the Empire and welcomed in others, and some of the subordinate ethnic groups have social systems a lot like Silbar does.

Officially the Empire has a State religion that is the Druidic practice, with ritual sacrifice of animals and at times men, but in practice the conquered peoples are usually allowed to go their own way on religious matters – or the Empire would explode. There is even an Imperial Edict requiring religious toleration, though it is sometimes honored only in the breech. There are more than half a dozen major religions within it, of which Silbar’s is actually by far the largest. The Imperial priestesshood is not happy about this and has been agitating (sometimes rioting) for more repression, even as they lose more and more followers in the new cities and towns to the Silbari faith. The recent Emperors have been buying them off with empty titles and lavish temple construction, and outright bribe-gifts, while ignoring their basic complaints.

Trade has been rising due to the Peace the Empire has brought, a peace that is enforced by Gwythlo legions but administered by Silbari-trained bureaucrats writing Silbari script and counting in Silbari numerals. The roads and harbors built by Klinto engineers for Gwythlo armies are fostering Silbari trade, which almost nobody in the Imperial Gwythlo hierarchy foresaw. This is causing a lot of social stress, as Silbar profits more than anyone else from expanding trade – but lots of other folks are prospering too. The resultant cash flow from this economic expansion has been vital to support the Empire’s military, but it’s also undermining the State through increasing corruption. This is damaging Gwythlo perceptions of their own virtue and indirectly their valor.

Thrown into this stress is the way that Gwythlo conquered Silbar.

The Story of The Conquest

Both Silbaris and Gwythlos tend to refer to the incorporation of Silbar into the Empire as “The Conquest”, as if there had never been any other. But Gwythlos put the emphasis on the first word, ‘The’, as if smugly declaring that this was their highest achievement. Silbaris put the emphasis on the word “Conquest”, reminding themselves of their national humiliation, for all of Silbar had never been conquered before (invaded yes, fully conquered no). The conquest was made doubly bitter in that it was aided by one of the brightest young Mages in Silbar’s history, Tagir – who defected to the Imperium and used his superior mage skill to aid it in the war. Tagir the Traitor knew a lot about the weaknesses of Silbar’s military magic power and exploited those mercilessly during the Battle of Black Pass. He got inside the Silbari Army’s communications-and-control-loop and by the time they understood how badly they were compromised, they had lost the battle and the war.

Yet what happened was actually a political marriage (a shotgun marriage, but still somewhat voluntary) between King Tunor’s only daughter Shyrill and Emperor Huon’s only son Brion. There was an epic sea-battle wherein Silbar’s navy was defeated by the combined Klinto-Fedaran navies led by Brion, and a huge land battle at Black Pass led by Huon which was followed by invasion. Huon and King Tunor killed each other in the Black Pass battle and the young Crown Prince of Silbar was also killed (Shyrill’s only brother). When King Tunor died the Silbari Crown teleported off his head, as it always did when the King died, and appeared on the stone seat atop the Hill Of Sight. Shyrill had been there using the magical power of the artifact under the Hill to follow the (disastrous) progress of both land and sea battles. When the Crown appeared on the special space atop the back of the seat, Shyrill felt it – and heard it call to her. She picked it up and set it on her own head, against normal precedent, and it accepted her. Silbar had a ruling Queen instead of a King; the Silbari people knew disaster must be at hand.

The Black Pass battle had beheaded both forces’ leaderships, with massive deaths among the warrior aristocracy. Silbar had mustered 500,000 men to defend Black Pass and over half of the male nobility was there to fight. Huon brought 1.2 million men from throughout his Empire to attack it. Over half of each force died in the battle that followed, but Silbar was decisively defeated. Shyrill knew it, and bargained with Brion to marry him (his first wife had died a couple years ago) and settle the war, though with large concessions. Even among the surviving Silbari aristocracy there was substantial dispossession and demotion in favor of victorious favorites of the Imperial Army (and to some extent, Navy). Many thought she had ‘betrayed the country’ despite her very clever playing of a very weak hand. Silbar should have lost much more than it did; she saved much from the wreckage, but got little credit for the fact.

The invading Imperial Army moved much more slowly after the Battle of Black Pass, bereft of its Emperor and with his replacement away at the sea battles. The land forces crawled forward, only getting as far as Sulmona and its sulfur mines before the marriage was arranged and consummated. This was well before either the capital city of Aretzo was taken, or any of the populous Valley cities north of it (though with the Imperial Fleet floating at anchor outside Aretzo’s Harbor, there wasn’t much doubt in anyone’s mind that the Capital city would have fallen). So most of Silbar saw the arriving Gwythlo Imperial troops show up as peaceful occupiers – which did not make the experience any less traumatic. The economic prosperity of Silbar was not laid waste by a sack and looting, but it was largely diverted for a while to feed Imperial coffers. Most of the Silbari aristocracy was deposed and downgraded, its castles and territory handed over to Imperials loyal to new Emperor Brion. There was impoverishment and hunger in Silbar during the early years, before Shyrill was able to persuade her husband to manage his newest and richest province better.

Part of the delay was due to rebellions and uprisings, which plagued Silbar for several years after the marriage of their young Queen to the new Emperor. However those were sporadic and local, mostly guerilla-based, and generally were simply not significant impediments to the new Imperial lords – serious nuisances, but not calamities. The bigger issue was tension over children.

The Story of Kirin and Terrell

Shyrill and Brion consummated their marriage in the Palace at Aretzo and he ruled from there for a couple months before heading back to Gwythlo with his new Queen-Empress in tow. She had immediately become pregnant. This was awkward because Brion already had a son by his first wife, a Klinto noblewoman; the son was Osrick and he was 13 years old at the time of the Conquest, and became upset when he learned that his father was bringing home a new wife.

Osrick was young but precocious, a very intelligent youth with some very large blind spots. He knew that primogeniture was not well-established in Gwythlo, he had cousins who could threaten his chance to inherit his father’s throne, and his new stepmother was fertile and already pregnant. The possibility of a herd of younger brothers to compete with him for his someday-crown gnawed at him. He began to court favor with Tagir the Traitor.

Tagir, having revenged himself upon the Silbari Mage Guild that had slighted him years earlier, was left somewhat adrift by the success of the Gwythlo Conquest. He had got his wish; but it wasn’t as satisfying as he thought, and the Queen had pulled a qualified victory from defeat by marrying Brion. Tagir knew his influence with new Emperor Brion would decline now. Osrick offered a chance to secretly sabotage the marriage, maybe cause the Queen to lose the Emperor’s trust. Tagir fell for it. They would assassinate the new child.

Shyrill’s pregnancy progressed; her Priestess-Healers reported that the baby was a boy, and healthy. But she was getting unusually large and the baby seemed to be positioned off-center in her womb, which was a cause for worry. Nobody understood that she was bearing twins – and one of them was undetectable. There was no precedent for this – Haroun’s Gift did not make its bearer invisible to spells, merely immune from damage. Until she went into labor a couple weeks early and produced two boys, nobody guessed she was carrying twins – but both Shyrill and her personal Healer, Dona Seraphina, had begun to suspect. So when the babies were born, Shyrill had been thinking about alternatives already. She knew her stepson wanted her baby dead. She had sworn her staff to secrecy but word of the twin birth was bound to leak out, too many attendants knew about it.

Her lady-in-waiting, Mairee Verhys, widow of Baron DiLione who died at Black Pass, had delivered herself of her own son Penghar less than a day before. Mairee already planned to return to Silbar to raise her infant on the family Estate. Shyrill begged her to swap babies and smuggle the undetectable newborn back to Silbar to be raised in secret, safe from Osrick.

Mairee agreed, swapped babies and took ship the next day for her home, with baby ‘Rillin’ in her arms. Tagir had been waiting and watching. Even so she almost escaped him because he could not detect the baby, and could barely detect her while she held him. She was on a small ship and many miles down the river before he figured it out. So he brewed a storm-spell and entrusted it to a demon summoned by a Gwythlo Druidess, then sent it after Mairee. The demon was concealed as a light breeze, commanded to pursue her ship and when it caught up, turn loose the storm and sink it. But she held the baby for three days, until the ship was well out to sea, never letting his skin be out of contact with hers except for brief moments, and so the demon was confused and hesitated, foiled and fruitlessly hunting. Until she set the baby down to sleep and went on deck for some air, and the demon located her and pounced.

The storm-spell had been bottled up too long; it rapidly grew out of control. It raged across half of the Sundering Sea and sank dozens of ships. Mairee’s ship scudded ahead for a time but finally succumbed to the crashing waves. Sailors tied her and the baby onto the broken mizzenmast as the ship foundered and they were swept away. She clung to the babe and his own magic kindled and covered them both – the demon could not find her. Knowing it had failed its command, the demon fled back to the underworld and abandoned its charge. The unnaturally-swelling storm caught the attention of dozens of mages, then hundreds, who didn’t need long to trace it back to its origin – and Tagir was accused.

He didn’t go quietly when the Emperor’s men came to seize him – he fingered Osrick, and spilled all he knew to Brion in a desperate bit to survive. And so Emperor Brion discovered that one of his Druidesses had summoned a demon to be used against his child, his wife Shyrill had kept a secret, his pet Mage Tagir was a traitor to him as well, and his Heir Osrick was a fratricide.

Matters could have gone badly for everybody, but Brion chose to be (somewhat) merciful. Shyrill was pardoned. Osric conditionally pardoned, contingent upon Osrick swearing a binding oath before all the nobles of the Empire that the surviving baby, Terrell, should have Silbar for his own with no duty to Osrick other than a set annual tribute. The druidess and Tagir were sentenced to harsh punishment.

This was more than Shyrill had hoped for. Her son was assured the Throne of Silbar, or at least a chance at it; the Crown might not choose him, but she had years to get him ready and could hope he would be judged worthy by Silbar’s God. It had cost her the life of her favorite lady-in-waiting and her firstborn son, the dark-haired boy, and for years afterward she would touch the black hairs of the child’s Birthlock that had been plucked from his newborn head. But no Mage spell ever located the child even using his birthlock. Given the strength of the storm he must be dead.

Baby ‘Rillin’ didn’t die. Nor did his ‘mother’, though she did suffer terrible trauma that caused her to lose her memory and her mind, regressing to a little girl mentality for six years. Child and ‘mother’ were found and rescued by the villagers of Pearl Island. They took the two in and raised the boy as one of them, giving him the name ‘Kirin’ or ‘Black Eyes’ in the old Silbari dialect that they spoke. They named her Ena which means ‘half’, for she spoke like a half-wit.

But the boy was different. To start, he was pale of skin, a sort of golden-brown rather than the walnut color of a Silbari. He had curly black hair, black as night, which none on the islands had ever seen except on a Xir trader. And he had pointed ears. He looked, indeed, much like the drawing of the Tormentor’s Imps from the waist up. Fortunately he did not have furry legs, hooves, or a barbed tail. The villagers got used to him, though the children would sometimes taunt the boy. The other village halfbreed, Caract, a man sired on a village woman by one of the Xir Traders, was black-skinned with curly hair too, he married Ena, adopted Kirin and raised him. Childhood was, if not quite as idyllic as a story, pretty close most of the time.

When Kirin was six a new Xir Trader came, and this one realized there was something extraordinary about the boy. He asked questions, learned that the salvaged mast and spar to which they woman and child had been tied was built into the village temple, and talked to Kirin’s ‘Mother’. He left very excited and promising to come back sooner than usual next time. But after he left the village was raided and the people enslaved by Klinto slavers.

Kirin and Ena were carried off; Caract was killed trying to defend them. She suffered a blow on the head and lingered near death for a day, then awoke – with her memory returned. She dared not tell Kirin who he was but used her charms on the slaver leader to make sure she and ‘her boy’ were kept instead of being sold apart. And she looked for a way to escape.

Kirin was allowed to run wild over the slaver’s hidden island base – there was no way to get off it. The slavers kept a few permanent slaves, generally leg-crippled men who couldn’t escape, to do the scut work and tend the base while they were away; a few slavers always stayed behind to watch over them. Kirin’s mother and one of the slave men plotted to escape – he knew how to build a coracle, which was possible on the island with the local wood (while carpentry of a boat was hopeless). In secret he did so, with Kirin’s help, and taught the boy something about sailing the thing. But on the night when they set out to escape, he was killed by one of the watchmen who hadn’t got quite as drunk as they thought he had. Kirin’s mother was badly injured by the man but Kirin used his Shadow for the first time to defend against the slaver. Ena and Kirin managed to escape in the coracle, and the slaver died while trying to swim after them when a shark attacked him.

So Kirin and his mother drifted with the current, not knowing where they were bound. She was delirious and sick most of the time from internal bleeding, babbling incoherently, and he could make no sense of the things she said. The current carried them through the islands – it was the westward-flowing counter-current driven by the main oceanic ‘gulf stream’ that flowed east along Silbar’s southern ‘Wild Coast’. A dozen times they should have been flung out into the main current and carried away from their goal, but always the counter-current deposited them into another one and another one, and they ended up in Silbar Bay across from the City of Aretzo. There Kirin struggled mightily with the one paddle and finally got them to the harbor mole, where they were carried through the Old Trade Gate by the tide and a wave from a spell-towed ship, and found themselves at the seediest dock in the most dilapidated part of Aretzo. Kirin was barely able to drag Ena out of the boat onto the dock, and tow her along into the alleys and streets while she staggered in a delirium haze of pain. The walk tore something half-healed inside her and she had to lie down on a pile of trash in an alley, where darkness found them. Terrified and lost in this big city, Kirin covered them with his Shadow so that they could hide during the night. And in her sleep, Ena died, still never having revealed to him who he was.

In the morning they were found by a man named Pater, who persuaded a corpse-taker to haul her to the Poor Field, and walked there with Kirin so he could say goodbye as she was buried in an unmarked grave. Then he questioned the boy, learned he had nobody in the city or in all of Silbar, and no hope with his skin and ears of ever being taken in by anyone respectable, or even by a temple orphanage (which tended to discriminate against the bastard children of the invaders).

So Pater brought Kirin to Mother Gee, a woman who ran a Faginy racket out of a wing of the Sulphur Serpent Inn where Pater lived. Kirin was taken in and lived with a dozen other orphan boys in a garret over the stables of the Inn. Mother Gee used him for errands and listening, and when he proved to be adept at worming his way through spaces, as a spy. He brought back much useful information for her, and she taught him the underside of Aretzo off which she made her living by judicious selling of information. She forbade her boys to steal, though a few of them did anyway (generally food), because she didn’t want trouble from the City Guard. For a few months Kirin grew into his new life, and pater regularly checked in on him. Kirin learned that the old man was an acrobat with the troupe that lived in the fourth floor of the Inn and practiced in the cavernous Attic. Sometimes when he had free time Kirin crept into the Attic and spied on the acrobats at practice. He loved what they did, and practiced walking on narrow boards and jumping and exercising. He dreamed that he might one day become an acrobat, but knew better than to ask – Pater’s father, who ran the troupe, hated Gwythlos and had only contempt for their bastard children. If he caught Kirin spying he would throw him out. Pater always argued with his father over that.

Then one day Kirin’s comfortable new world ended. The Imperial Governor, Caddoc Ap Marn, sent his troops to seize every vagabond child on the streets who couldn’t provide a home address. Kirin and fifty others were dumped into a cell, and then tattooed with slave numbers and sold on a slave block.

Slavery was illegal in Silbar by ancient law, but the Imperial Governor thought he was above such laws. The boys were sold to foreign residents, many of them Gwythlos or Klintos resident in the city, and Kirin and two others found themselves in the possession of a Gwythlo merchant with monstrously evil tastes. They were chained in a basement with no windows, and their owner demonstrated that he was a sadistic pedophile who could only get sexual satisfaction while torturing boys. He had one prisoner still surviving from his previous acquisitions, brought secretly to Silbar after purchase elsewhere. The poor tortured boy whispered to the three of them in the dark that first night, sobbing out the terrible things that had been done to him. Then the next day the sadist tortured the boy to death while he raped him in front of the others, so that they could see what was coming. The man clearly enjoyed their fear and suffering. He let them scream as much as they wanted, informing them that there was a silence spell on the house so that nobody could hear them. Kirin screamed himself hoarse, and as promised, nobody seemed to hear.

Kirin had never been more terrified. Through the long day and longer night that followed he struggled with his chains until his wrists bled, but the manacles were well-designed and would not come off. They could only be unlocked with a key and he had nothing with which to pick a lock even if he had known how. Then the second night the sadist came back for them, and chose Kirin as his next victim.

The man unlocked him – Kirin tried desperately to escape but the monster was much too strong. The man tried to clamp him into the torture-and-rape rack and Kirin, in ultimate despair, finally called upon his Shadow. It came forth and killed the man, and Kirin knew for the first time in his life the sickly-sweet taste of a terrified soul slipping through his Darkness into eternity.

Somehow he found the coherence to take the keys and release the other boys. Somehow they found a way out of the basement and into the house above, and escaped the man’s deaf servants to run out into the street. The other two boys fled while Kirin wandered half-delerious and naked – his clothes had been stripped from him before the man unlocked him and he hadn’t thought to grab any rags to cover himself. And there, against odds, Pater found him. The acrobat had found out who had bought him and was trying to figure out a way to break into the house when he discovered Kirin already free. The boy’s wounds where his clothing had been cut off and the chains had chafed his wrists raw, told their own story. Pater took him to a Temple, got pants for him from a Poor box, and fed him by buying a baked fish-pie and oranges. It was hours before Kirin recovered enough to let Pater carry him back to the Sulfur Serpent, where Pater had harsh words for Mother Gee not moving faster to save him. Then Pater took him into the Sulfur Serpent and led him upstairs to the Attic, and told his father that Kirin was joining the DiUmbra Acrobatic Troupe.

While the men argued, young Sevan, two years older, took Kirin into the Attic and showed him the low-rope where the young DiUmbras practiced. Sevan’s sister Maia sniffed at his clumsy attempt to walk it and showed him up by walking it herself. So Kirin had to try harder, and got farther the second time. So Maia had to do it better still, and back and forth they went with Sevan laughing and cheering both of them on. Kirin didn’t know it but that was his seventh birthday. Before sundown Pater out-stubborned his father and Kirin was admitted into the DiUmbra troupe as Pater’s adopted son. The next day they went to a black-market tattoo artist that catered to the Herdae sailors (who flaunted tattoos openly even though Silbaris thought them a horror) and got a fraudulent manumission line and date tattooed over the slave number. Then they went to the temple and Pater adopted him formally. From then on Kirin joined the DiUmbra family, and though the Old Master glared at him often and assigned him all the scut work, Kirin had a home.

He grew into it joyously, for the DiUmbra clan loved each other as only an extended family can – amiably bickering, shouting, arguing, sharing, and loving. He learned to walk tight-ropes and do acrobatics, and proved to be so gifted that they soon put him in the act. At first they covered up his ears and darkened his skin with make-up, to minimize his half-breed appearance. But eventually Pater found roles for him in plays they had rarely done, and Kirin played many supporting roles in the family’s productions, as well as serving as a general tumbler. He was short for his age but put on plenty of muscle, and by the time he was fifteen he could do even the flying somersaults that were the family’s signature accomplishment. He was too small to become a catcher, but he did become a star flyer, with Sevan as his catcher.

All the time Maia teased him and treated him just like her brothers.

While practicing the men wore tights that covered them from ankle to waist, and nothing else. The women wore longer tights that reached to their shoulders, hiding nothing of their female forms. During productions they both would dress in fancier garb, often with body paint and sometimes even wigs. Other Silbaris regarded acrobats as a bit scandalous, and a half-breed acrobat as even more scandalous, even though they came to their shows. The DiUmbras reacted to this with quiet defiance and a drawing together that kept Kirin safely inside as one of the family.

Then Pater discovered a script for ‘Malik and Mercia’, a play featuring an Imp and an Angel. Kirin was perfect for the Imp. His voice had begun to change a few months earlier and mercifully settled quickly into its adult range, which proved quite good for singing the Imp’s lines. And his beard had begun to grow, as silky black as his hair. He could do this – his first starring role.

Maia played the Angel. Kirin found that his role in the play was to seduce her away from her Seraphic mistress so that the tormentor might capture her as his own. He knew nothing about being a seducer so the whole family had to teach him how to play the lines. He learned fast, and he and Maia danced with her levitation talent swirling white gauze handkerchiefs through the air while he danced his Shadows among them. Most of the audience thought it only a clever trick and never guessed that they were seeing Living Shadows being manipulated.

The production was a tremendous success. The DiUmbras made pots of money from it, so much that they could eat meat with every meal, a rare treat. But then near the high point of the production, Kirin discovered he had become a man, and fell in love with Maia as a woman.

The show suffered at first. They were too conscious of each other’s bodies, too self-conscious, and so they made mistakes. But they figured it out, got back to their superb performances – and then became lovers. They concealed it for two whole weeks before the rest of the family found out.

Old Master was furious. But Maia’s father declared simply that he would be delighted if they married and Kirin became his son as well as his brother Pater’s. And so they did, with a small temple ceremony and a feast and a new room in the Inn - for both of them, the first time that they hadn’t had to share a room with the family’s other unmarried boys or girls. Their love gave the act a new richness and attendance soared again.

But then . . . .

(Break – here are the events of “Shadow and Light”.)